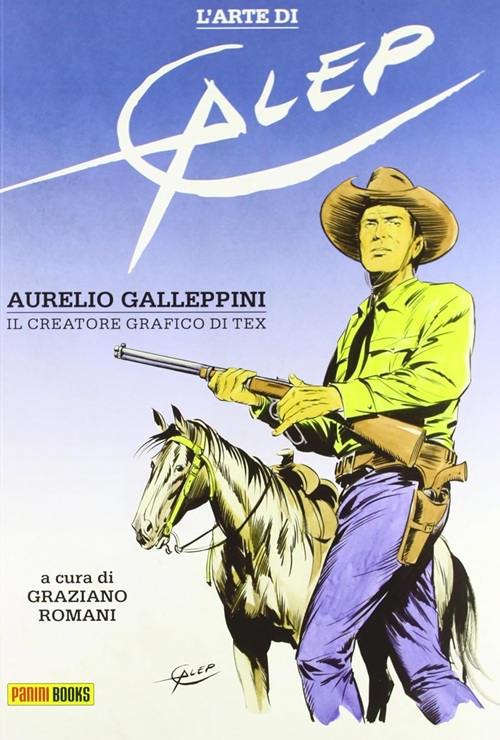

Aurelio Galleppini, an artist whose very name became synonymous with the adventurous spirit of the Italian comic book, carved an indelible mark on the landscape of sequential art, his legacy etched most profoundly in the enduring saga of Tex Willer. Born on August 28, 1917, in the small Tuscan village of Casal di Pari, to Sardinian parents, Galleppini, affectionately known by his nom de plume Galep, embarked on a creative journey that would span decades and captivate generations. His early life, largely spent on the rugged island of Sardinia, instilled in him a deep appreciation for the natural world and, notably, a burgeoning fascination with horses, a motif that would gallop through much of his later work.

Unlike many artists of his stature, Galleppini was largely self-taught, eschewing formal academic training after only two years at an industrial institute to pursue his innate passion for drawing and painting. This autodidactic path allowed him a freedom of expression and a unique stylistic development unconstrained by conventional schooling.

His professional artistic career began remarkably early. By the tender age of eighteen, his talent had already found a commercial outlet, with his drawings appearing in animated cartoons produced for a German projector manufacturer. This initial foray into the visual arts quickly led to his first published illustrations in 1936, gracing the pages of “Mondo Fanciullo” with enchanting fairy tales.

The late 1930s saw him further hone his craft and expand his repertoire, contributing extensively to periodicals such as “Modellina” from 1937 to 1939. During this period, he brought to life illustrated tales like “In terra straniera,” “La prova dei coccodrilli,” “All’ombra del tricolore,” and the expansive, color-rich comic album “Le avventure di Pulcino.” His versatility was evident as he also designed striking covers for “Il Mattino Illustrato” and provided artwork for Andrea Lavezzolo’s “Il segreto del motore.” A significant collaboration during these formative years was with the renowned writer Federico Pedrocchi, yielding the long comic-strip stories “Pino il mozzo” and “Le perle del mar d’Oman,” published by Mondadori. These early works showcased Galleppini’s burgeoning skill in narrative illustration, laying the groundwork for the epic tales he would later visualize.

The year 1940 marked a pivotal shift in Galleppini’s life and career as he relocated to Florence, a city steeped in artistic heritage, where he began working with the publishing house Nerbini. Here, he produced several comic strip stories for “L’Avventuroso,” for some of which he even penned the scripts, demonstrating his comprehensive understanding of comic creation. However, the oppressive shadow of Fascist censorship loomed large over Italy’s cultural landscape. The regime’s absurd dictates, which distorted the content and form of comic-strip narratives, compelled Galleppini to temporarily withdraw from the field that was rapidly becoming his calling. This enforced hiatus, spanning the war years and the immediate post-war period, saw him pivot his artistic energies.

He dedicated himself to painting, achieving noteworthy success in this medium, designing posters, and imparting his knowledge through teaching drawing. During this time, he was a guest of the Vincenziane nuns in Cagliari, where he created several significant religious works, including four canvases, a cycle of paintings, and fourteen Stations of the Cross for their institute’s chapel, works he would only sign much later in his life. This period, though a departure from comics, undoubtedly enriched his artistic sensibility and broadened his technical prowess.

The post-war resurgence of Italian popular culture provided Galleppini with the opportunity to return to his passion for illustration. In 1947, he re-engaged with the comic world, producing a series of albums for “L’Intrepido,” including titles such as “Il clan dei vendicatori,” “Il corsaro gentiluomo,” “Il giustiziere invisibile,” and “La perla azzurra.” Beyond original comic narratives, he also lent his illustrative genius to beloved literary classics, creating visual interpretations for “I tre moschettieri,” “La maschera di ferro,” “Le mille e una notte,” “Il barone di Münchhausen,” and even a comic-strip adaptation of “Pinocchio.”

It was at the close of 1947 that a fateful connection was forged, one that would forever alter the trajectory of his career and the landscape of Italian comics. Galleppini established contact with Tea Bonelli, the astute director of the “L’Audace” press, proposing a renewed collaboration. This meeting culminated in the creation of two new comic series in 1948, both conceived by Tea’s former husband, the prolific writer Gian Luigi Bonelli: “Occhio Cupo” and “Tex Willer.” While “Occhio Cupo” struggled to find an audience and was soon discontinued, “Tex Willer,” initially a modest venture, would gradually, yet inexorably, ascend to become an unparalleled phenomenon in Italian publishing. To facilitate this burgeoning partnership, Galleppini moved first to Milan, residing in Tea Bonelli’s editorial-house, and then to Liguria, immersing himself fully in the demanding creative process. In the early days, his work rhythm was relentless, dedicating entire days to “Occhio Cupo” and the nocturnal hours to “Tex,” a testament to his unwavering commitment.

Tex Willer swiftly became the cornerstone of Aurelio Galleppini’s artistic life, a character with whom he formed an almost symbiotic relationship. From its inaugural issue in 1948, Galleppini dedicated himself body and soul to the adventures of the rugged ranger. For many years, he was the sole artist responsible for illustrating Tex’s thrilling exploits, a monumental undertaking given the comic’s burgeoning popularity and demanding publication schedule. His prolific output was legendary; he single-handedly drew countless pages of Tex stories and, perhaps most remarkably, designed every single cover for the regular series right up to issue number 400. This incredible feat of consistency and dedication is a record of which he was immensely proud.

As the success of Tex Willer exploded, necessitating an ever-increasing volume of material, the sheer scale of the enterprise eventually called for the assistance of other talented illustrators. Artists such as Guglielmo Letteri, Francesco Gamba, Giovanni Ticci, and Erio Nicolò joined the production team, contributing their own artistic interpretations to the Tex universe. However, Galleppini’s guiding hand remained paramount, particularly in the iconic cover art, ensuring a visual continuity and a distinctive aesthetic that defined the series. His commitment to Tex was so profound that any pauses from the character were rare and exceptional, such as his work on “L’Uomo del Texas” in 1977, a standalone tale scripted by Guido Nolitta for the “Un Uomo, un’Avventura” series. This unwavering devotion cemented Tex Willer’s place as not just a character, but a cultural institution, inextricably linked to Galleppini’s artistic vision.

Galleppini illustrated a special poster in Italy in 1970 titled “L’Uomo Mascherato Visto Da Galep” (The Masked Man Seen By Galep), which featured his depiction of The Phantom in his red costume (as often seen in Italian comic books). This poster was part of a set of four, with the other characters being Flash Gordon, Mandrake the Magician, and Prince Valiant – all iconic King Features Syndicate characters.

Galleppini’s artistic style, often referred to as “Bonelliano” due to its association with the publishing house, was characterized by its clarity, dynamism, and robust realism, making it perfectly suited for the Western genre. His lines were clean and expressive, capable of conveying both the raw energy of a gunfight and the subtle emotions of his characters. He possessed a remarkable ability to render detailed environments, from the vast, dusty plains of the American West to the intricate interiors of saloons and frontier towns. His early fascination with horses translated into masterful depictions of these animals, capturing their power and grace with an authenticity that few other artists could match.

Galleppini’s art was not merely illustrative; it was storytelling through visuals, guiding the reader seamlessly through Bonelli’s narratives with a powerful sense of momentum and atmosphere. He established a visual standard for the “Bonelliano” format, which typically featured complete stories presented in over 100 black-and-white pages in a compact pocket-book size, focusing predominantly on adventure themes. His influence extended far beyond Tex, shaping the aesthetic sensibilities of an entire generation of Italian comic artists.

Throughout his career, Galleppini received numerous accolades, including the prestigious U Giancu’s Prize in 1993, a testament to his significant contributions to the art form. His passing on March 10, 1994, in Chiavari, marked the end of an era for Italian comics, but his legacy, embodied in the enduring popularity and iconic imagery of Tex Willer, continues to ride across the plains of imagination, a testament to the master illustrator whose pencil brought the Wild West to life for millions.